Continued from yesterday:

Ah, what was Hope always saying? Life is a beach? He hadn’t quite understood her before, but now he did and it surely was. Life is a beach. But it isn’t any pure coral white beach, with sunny skies and clear azure waves. It’s just an old beach of a beach and then you die.

Fuck.

Prem rarely used profanity, so when he thought this word, it appeared in his mind separated out, as if in a paragraph of its own, highlighted, in bold.

Fuck.

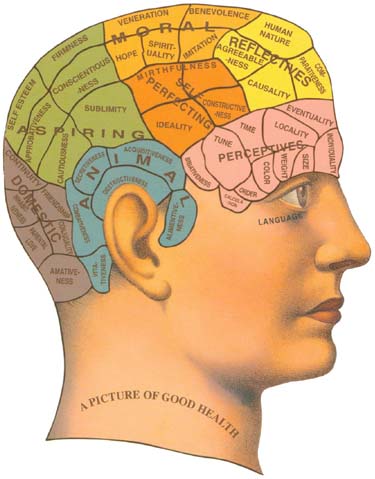

What was the point in living if you were only going to die, ignominiously, and end up with your toe tagged in the morgue like any television corpse. It hardly seemed worth it. What was he doing, why did he bother worrying about all these people in Building 22, who were just going to die and end up tagged at the toe themselves? How was it worth it, trying to hold the building together that was trying to fall apart after a hundred years of being mortared and bricked into existence? And how worth it was it anyway, just to upkeep a community of twelve individuals who many of them had rarely-to-never paid a cent into society, but only drew from it like the proverbial parasites that some, like Martin the skinhead, called them.

Martin had hardly a peg-leg to tap out that tune with, however, being something of “parasite” himself, Prem observed. But being copper had never stopped one saucepan from calling another tarnished, not in Prem’s experience. And just why hadn’t the disabled paid into society? Had any of them ever tried to get off disability? Was it their fault? Or was it the fault of a society that encouraged, even forced permanent disabled status on them, and with it concomitant poverty? Who could get out of the disability snare once caught in it? No one who had lived in Building 22 had ever, so far as Prem knew, outgrown or out-earned disability. In fact, the residents were forever finagling ways to earn just up to, but not beyond the strict earning limits placed on them, just so they could maintain disability and their subsidies and their small but stable incomes.

What a miserable trap. You could get a regular but miserably small income for life, if you agreed to be disabled by the system. But in order to get out of the trap, in order to try to earn a living and make your own way, you would in a stroke lose both the place you lived and your regular income, all for a life of insecurity and instability. And this at a time when nothing was secure or stable except the fact that there was no safety net, and no one cared about people in need except a handful of overused charities and churches. So who could blame a disabled person for deciding not to even try to work but to stay on disability and remain impoverished? Who could blame them when that meant at a minimum a roof over their heads and food on the table. It was a devil’s bargain, but Prem could see how sometimes the devil could appear a better partner than the faceless ghoul of potential homelessness and hunger.

“Earth to Prem, earth to Prem,” called Ernie while Beanie smacked her bony hands and made a resounding clap in the tiled lobby, startling Prem from continuing his thoughts. He stared at them, realizing that of course the two women in their own persons made hash of his argument: They had both had had long working lives and deserved more rather than less of what they got out of the system. Nevertheless, it did not completely detract from his argument that two elderly women on social security were trapped in poverty just as the non-working disabled were.

“What were you thinking that took you so far away?” demanded Ernie, never one to keep questions to herself.

“I, I,–“ Prem didn’t know how to respond.

“Aha! You really were thinking something. It must have been juicy!” Together the two ladies crowed.

Suddenly, Prem decided to take the question seriously. “Actually I was thinking about something. It wasn’t juicy, not the way you think, but it was – I don’t know how to put it. Can I ask you a question?”

“Sure.” The two spoke at one time.

“Okay, then. Tell me when you disagree with me. First of all, this is a society of “haves” and “have-nots,” right? I mean, we have huge inequality, you can see it right here — this building, Number 22, compared to others down the street is just one example.” Prem stopped as if one of the women had spoken. But he saw at once that they were simply waiting for him to go on so he continued, “Clearly it’s no good simply to give a “have-not” everything he or she needs. That’s just what we do now, and in my opinion it leads nowhere but to misery and protracted disability.”

“What if the “have-not” isn’t disabled, but just old? What if the “have-not” works full-time but isn’t paid enough to live on? There are a lot of other ways to be a “have-not” than to be disabled.” These objections came from Beatrice Bean, whose fingers held an imaginary cigarette. She pretended to suck on it, then flick the ashes.

“You’re right. I guess I am a little obsessed with the disability issue. But let me go with just that part of it. If the “haves” somehow could help the disabled “have-nots” gain a set of skills – any set of skills — to become “haves” like themselves, wouldn’t that be better? There are plenty of skills that can be marketed. You don’t need to go to a regular workplace these days to earn a living.”

“I really hate that word, ‘marketed’,” Ernie interjected. “Why does everything have to be for sale? Why must everything be reduced to a matter of money?”

“Because it’s a capitalistic world, that’s why. You and I may not agree with it but we’re stuck with it, and until we can live in a world without money, the have-nots need to learn how to earn.” For all the conviction in his voice, Prem was not that comfortable defending capitalism, especially knowing how avarice had despoiled the natural world he loved so much. But he knew that capitalism had ruled for centuries, and that it wasn’t going to change in his lifetime or the lives of these two women, so it was to all intents and purposes, a fact of life.

“So you are going to teach all the disabled people in Building 22 how to get a paying job? Good luck!” said Beanie with a wry smile. “I don’t personally think anyone here is going to thank you very kindly for it.”

“But don’t you see? That’s precisely what I mean.”

“What do you mean? Why should anyone thank you? If you have an apartment, a social worker, food stamps…you have it made in the shade. Why should you want to work?”

“Because people would feel better about themselves if they could work, that’s why…” Prem said, lamely. He then realized that he had made the mistake of so many do-gooder liberals, believing he knew what was good for those he wanted to help better than they did themselves. But how could he know how they felt without asking them? How could he know whether they felt bad about themselves now or would feel better about themselves working? He hadn’t spoken to most of the residents about the matter. In fact, it had only been Hope, the second floor resident and artist, with whom he had spoken in any depth. It was she who had been so passionately outspoken about feeling trapped in “the System.”

Even as he thought about it Prem realized that things were complicated. Yes, Hope was an artist, and he felt she should be able to sell her work and keep the income at the same time, but wasn’t she also often ill and unstable? It seemed to him that she was hospitalized for weeks at a time, and as frequently as twice a year. What would she do without disability payments when she was ill, he wondered, and how would she survive or cope even as an artist during the inevitable lean times if her disability payments were cut off? Yet she was the tenant who resisted staying on disability, even as it was clear to him that she could not afford to chance getting off it, not unless she could sell paintings regularly or for large sums of money, something that was not likely to happen. People like Hope weren’t discovered by museums or fêted by the rich and famous to be made rich and famous. No, they simply did art and made art alone, steadily, keeping the faith that it was worth it simply because art to them was like food for the rest of us.

Hope wasn’t going to quit painting or making her sculptures just because no one “discovered” her. Hope did art because she had to do art or die. Period. If it sold, well then, good. But so far as Prem knew, Hope had never tried to advertise or sell in the manifold ways that “working artists” sold their art: by marketing themselves and their art in such a way that people come looking to buy. It wasn’t that she would not sell. Prem thought she might be very happy if someone wanted to buy a piece of her artwork. It was simply that she had other things on her mind than making art in order to suit the purchasing public. And what about the others in Building 22 – were they so very different? What did he know? Did he know enough to draw any conclusions at all?

“It’s just such a vicious cycle,” he said, as if finishing a thought he had started aloud.

Beanie seemed to have followed him. “Yah, I agree. But some of these folks have two or three strikes against them before they started out in life. Can you blame them for seeing a tiny fixed income for life better than the insecurity of not knowing whether you can earn anything at all?”

Ernestine Baker seemed to disagree. She counted off on her fingers, as if reciting a litany, “Darryl, Kashina, Bryony, Giorgio, Feder…and that strange woman, Hope. What cases. I wouldn’t want to be in their shoes for a second. I can’t imagine being one of them for a day, not even if you paid me. Talk about unfulfilled lives and unrealized potential!”

“But what are you saying?” remonstrated Prem. “That their lives are wasted? And if they are wasted, whose fault is that? Why have the disabled been allowed not to do something with their lives? That’s my entire point. Look at Giorgio. He was a talented auto mechanic. He wasn’t in the system all his life. He has skills. He just can’t use those skills right now. Feder has savant expertise that surely could be used somewhere productively. Bryony already works three days a week, and Kashinda is so young that it would indeed be a terrible waste if she never learned to do something with her life, except smoke pot. We created a real monster with Federal disability benefits: the same limitations that promote permanent poverty promote never getting better.” Prem could feel himself getting passionate, and wondered just where that came from. Why did he care so much? Why he sounded almost hysterical…

“Okay, what’s going on, Prem?” asked Beanie, peering at him with more than a little concern. “Why don’t you draw up a chair, sit down with us, take a load off…”

Baker, abashed, chimed in, “You want a drink, Prem? The beer is on me.”

His face warm, Prem had felt a sudden but urgent need to be gone. To be anywhere but here. Ashamed of himself, he apologized to the two older women and literally backed away even he spoke, forgetting entirely why he had returned to Building 22 at such an hour in the first place. By the time he remembered the water pressure situation that had occurred just that morning, he was halfway down the block with an old cassette tape playing Dave Mallett’s “Pennsylvania Sunrise,” a song that always made him yearn to hop a train and go places, never to return.

Pennsylvania sunrise…ten degrees at best.

Peerin’ from the window of a club car heading west.

After mornin’ glory…money for the miles.

Someone said I’ll do this for a while.

_____________

I promise more action in the segments I will share in upcoming days. I won’t share the entire novel but I will share some parts of it, enough to entice. I now have c 120 pp. double spaced 37000wds.